En español, en français, em português.

In hotel distribution, attention usually falls on the pricing strategy (“the what”), leaving the connectivity architecture (“the how”) in the background. However, the ability to maximize revenue directly depends on the technology that carries these prices.

Technically, there are two standards for connecting the hotel ecosystem (RMS, PMS, Channel Manager and Booking Engine) with sales channels: PDP (Per Day Pricing) and OBP (Occupancy Based Pricing). Neither model is intrinsically superior; they are two different ways to achieve the same goal with different operational implications.

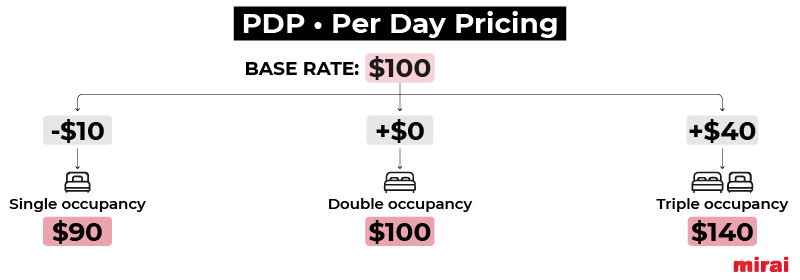

PDP (Per Day Pricing): rule-based pricing model

This model is the industry’s historical standard, designed to optimize operational efficiency and data transmission.

- What exactly is it? It is based on a primary pricing system: there is a lead rate (the base), and all other rates for different occupancies depend on it. These are not independent prices; they are automatically calculated based on the primary rate.

- How does it usually work? The hotel sends a single price (typically the Double room rate) from its system (PMS or Channel Manager). From that point, the Channel Manager usually handles the calculation: it applies a fixed rule (e.g., Base + €30 or Base – 10%) to automatically generate prices for singles, triples, or children. In some cases, this calculation rule may even be managed directly within the OTA’s extranet.

To understand the limitation of the PDP model regarding seasonality, it is necessary to observe how the large platforms operate.

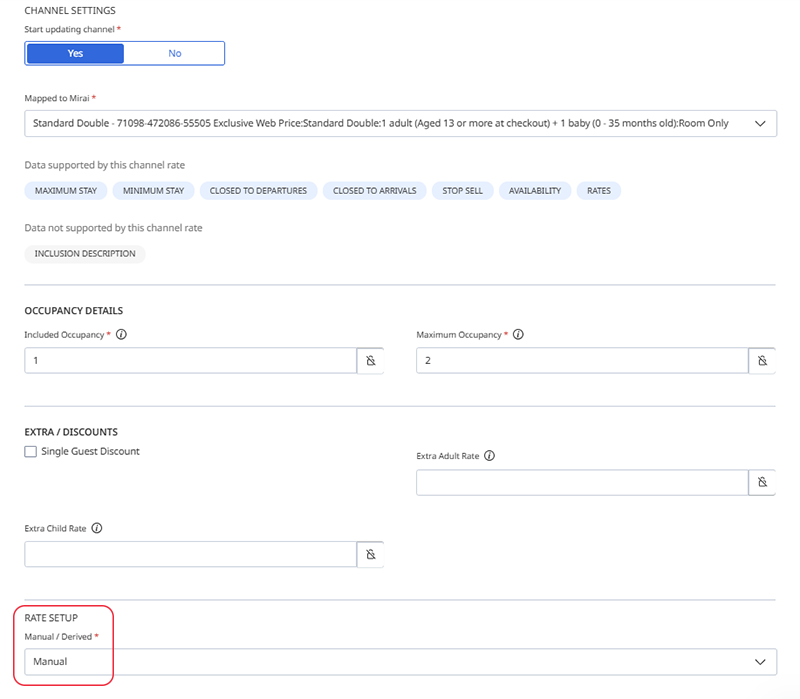

- In Channel Managers: the price per day (PDP) model is usually handled in two ways::

- Manual Management: total control, but slow management.

You decide the exact price for each occupancy (single, double, triple). It is highly precise, but if you change the primary price, the others do not update automatically, which results in a much higher workload.

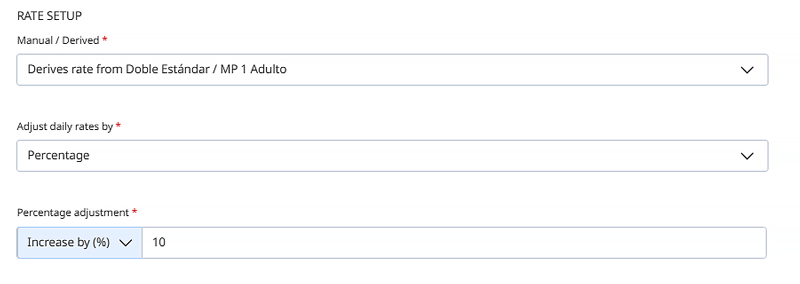

- Derived Management: speed, but less flexibility.

It is the most common option because it works automatically. You define a base price and the system calculates the rest following a fixed rule (for example: “add €30” or “add 10%”). The problem is that, being a rigid rule, it does not adapt well to changes in demand for each season.

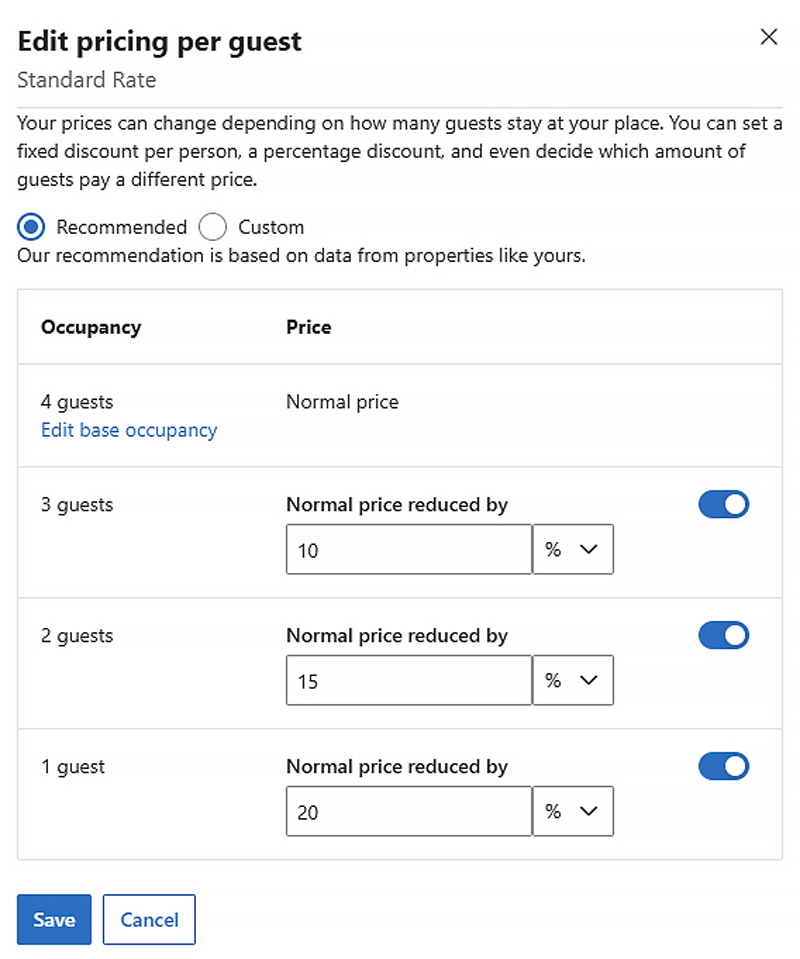

- And how do OTAs handle it? In most cases, the standard configuration is designed under a fixed price rule (supplement or discount) that does not automatically vary with seasonal demand. OTAs that allow seasonal supplements usually require constant manual management that increases the operational workload.

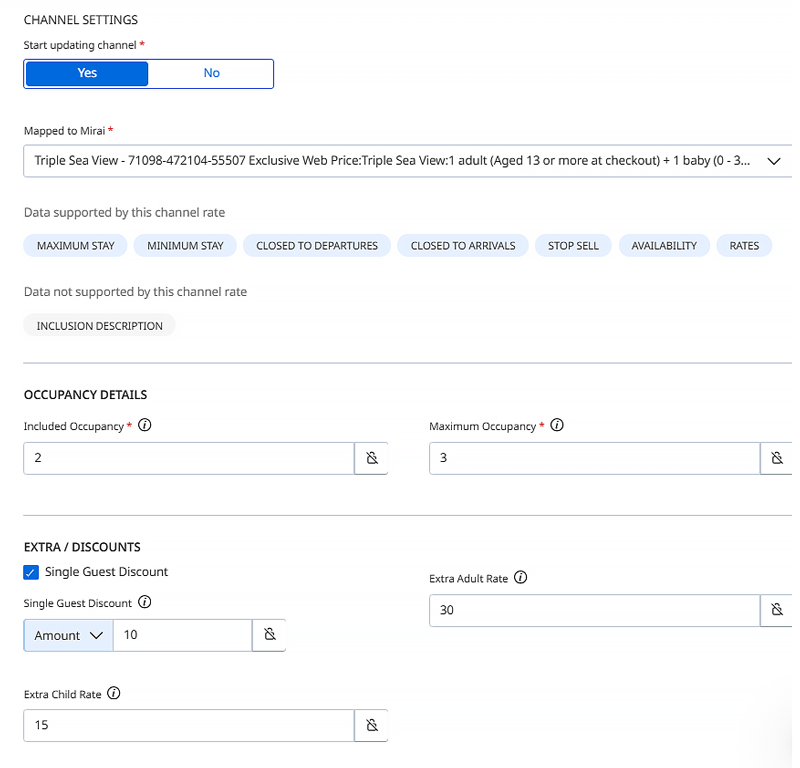

This is an example of the occupancy variation configuration in an OTA’s extranet. The channel allows setting a base occupancy and a fixed reduction for occupancies below the base occupancy.

Although overrides exist (the ability to manually overwrite a derived price for a specific date), in both Channel Managers and OTAs, these do not solve the structural problem. They function as a patch for specific exceptions, but relying on them for a dynamic revenue strategy would require constant monitoring, falling back into the trap of manual oversight, which is impossible to manage at scale.

- Where is the calculation decided? Here lies the key. Although the base price is born in the PMS or the Channel Manager, the calculation rule is usually delegated to the Channel Manager or, depending on the flow, to the channel or booking engine itself. If it remains ‘hijacked’ by the OTA’s own extranet rules, it limits the hotelier’s real control over their own final price.

The most advanced RMS are designed to calculate prices by occupancy (OBP) independently, but they are often forced to export in PDP format due to ecosystem limitations (PMS or Channel Manager). Ultimately: your revenue strategy will always be limited by the weakest link in your connectivity chain.

- The great advantage of derived rates is efficiency: you manage a single price and the rest update automatically in a cascade. However, a common mistake is trying to “force” the model: if you end up creating as many rates and meal plans as there are occupancies, you destroy that efficiency and end up with an unmanageable system that remains just as rigid as before.

- What are its limitations?

Reservation delivery mapping. By delegating the price calculation to the channel or Channel Manager, the “return journey” of the reservation is more complex.

The chain effect and its downside: when you move the base price, you inadvertently drag all the others with it. Since these rules are usually fixed (for example, the same €30 supplement all year round), you cannot adapt to the actual demand of each season. If you want to increase the triple room rate, you are forced to increase the double room rate as well.

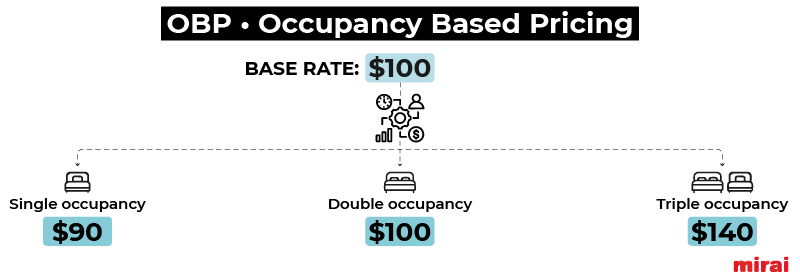

OBP (Occupancy Based Pricing): Independent pricing for each occupancy

This model represents the evolution towards data granularity, treating each occupancy as an independent product.

- What does this model represent? It breaks the hierarchy of derived prices. Each occupancy has its own final price, unique and detached from the others.

- How does this model work? Tthe system does not send calculation instructions (“Base + €40”), but absolute data: “Single: €90”, “Double: €100”, “Triple: €130”.

- Who controls the final price? It resides in the system that generates the price (RMS, Channel Manager or advanced PMS), and is transported explicitly. However, these prices often originate from linear calculations at the source.

However, there is a crucial difference in the channel’s intervention capacity:

- In the OBP model, the major platforms (OTAs) simply display the exact price you send them, without performing any calculations on their own. This ensures that the guest sees exactly what you have decided in your system.

- The booking engine as the final word: an advanced booking engine allows intervention. It can act by overwriting the received occupancy logic, replacing the linear increments from the PMS or Channel Manager to adapt to dynamic demand curves.

The RMS challenge: RMS can calculate and send all these final prices, but they require exhaustive mapping of all occupancies for the strategy to be executed correctly.

- What are the advantages of this model?: control and granularity. Allows defining specific strategies for each occupancy (independent elasticity) before distribution.

- What is the main limitation?: data density and mapping. Requires technology capable of processing a much higher volume of information, as each occupancy requires its own unique identifier (Rate ID). It is like moving from managing a single key for a room to managing a different key for each person who enters. If the channel is not natively OBP, this forces the creation of “mirror rates” that can saturate inventory management.

How much extra work does each model involve?

The difference lies in the volume of data to be monitored:

- In PDP (Management by exception) and using derived rates: 10 base prices are monitored (for a hotel with 10 room types). Variations are applied automatically.

- In OBP (Management by product): 10 rooms x 4 occupancies = 40 independent final prices are monitored.

The multiplier effect: this number can grow combinatorially when crossed with different board types (Room Only, Breakfast Included, Half Board) and cancellation policies (Flexible, Non-Refundable).

The operational balance

Scenario: A hotel with 10 room types x 4 occupancies x 2 meal plans x 2 cancellation policies:

| PDP Model (Efficiency) | OBP Model (control) |

| 10 base prices. | 160 independent prices. |

| You update the “Base Price” and the system does the rest. | Each combination requires a specific price. |

| Advantage: extreme speed, simple mapping, and total control over the “parent price”. | Strengths: maximum profitability per occupancy and total flexibility based on demand. |

| The toll: rigidity. If you want to change a child supplement only for August, you can’t. | The toll: massive workload. The risk of human error is multiplied by 16. |

The risk of false agility

Without automation, the granularity of OBP becomes an operational vulnerability. The likelihood of human error makes manual control unfeasible.

Many hotels try to “escape” PDP’s rigidity by creating dozens of independent rates in their PMS. The result is the worst of both worlds:

- They lose PDP’s agility (rates no longer update in a cascade).

- They don’t gain OBP’s intelligence (they still lack occupancy-based insights).

- Inventory hypertrophy: hundreds of rates that must be mapped and monitored one by one.

Comparative table of architectures

| What’s changing? | PDP (Per Day Pricing) | OBP (Occupancy Based Pricing) |

| Focus | Room management: occupancy is a secondary attribute. | Product management: each combination is a unique item. |

| Pricing logic | Derived: base rate + fixed rules. | Explicit: exact final prices. |

| Revenue Management | Linked: modifying the base alters all occupancies. | Independent: elastic optimization by occupancy. |

| Maintenance | Rule supervision: requires monitoring the calculation. | Mass management of final prices. |

| Connectivity | Rate aggregation: simplifies inventory but limits differentiation. | Native: direct connection of real inventory. |

| Consistency | Interpretative: risk of disparity due to external calculation in the channel. | Exact: the channel shows the specific data. |

| Usage profile | Hotels prioritizing loading agility and automated maintenance. | Hotels with complex inventories or granular revenue strategies. |

Why is the traditional model still the most widely used?

Even though the occupancy-based system (OBP) is more accurate, the per-day pricing model (PDP) remains the most common out of sheer practicality:

- Habit and stability: for years, priority was given to fast, error-free connections over detailed pricing granularity.

- Channel design: major platforms (such as Booking.com or Expedia) are built to handle this model efficiently. For most hotels, it is a robust and easy-to-manage solution, while the occupancy-based model remains the next step for those seeking total precision.

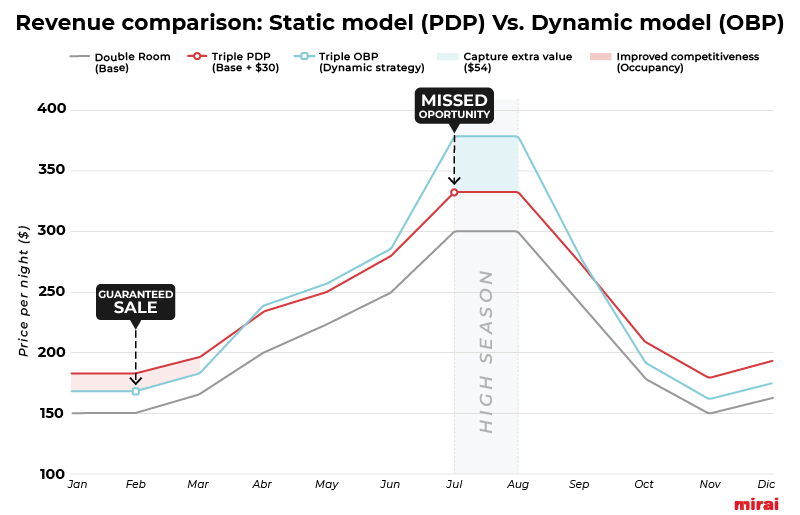

Real-world example: the revenue you lose due to rigid technology

Assumption: Double Room at €300 in high season.

- Scenario A: PDP Model (static rule) The 3rd person supplement is fixed in the Engine/Channel (+ €30).

– Final Triple Price: €330

– Consequence: to raise the Triple, you would raise the Double and lose competitiveness. Or worse: you would be forced to close the sale of the triple room to avoid underselling, losing total occupancy simply due to system rigidity.

- Scenario B: OBP Model (Dynamic strategy) High family demand is detected. The Triple is set at €375, keeping the Double intact.

– Final Triple Price: €375

– Consequence: an additional value of €45 per room/night is captured.

Financial projection:

Assuming an average occupancy of 100% and extrapolating this difference to an inventory of 20 rooms for 60 days of high season, the gross revenue differential amounts to €54,000. In the PDP model, this revenue is not captured due to the limitation of the general rule; in OBP, it is the direct result of a specific pricing decision. And more importantly, in PDP, by raising the price of the triple, you might “price yourself out of the market” for the double (which is usually the best seller).

And this is only for one room type; the margin is exponential if you consider the rest of the occupancies, boards, rates…

The balance between architecture and strategy

In the end, the choice between PDP and OBP is not a matter of which technology is better, but of what level of granularity the hotel’s operations can absorb without losing control. While PDP offers a simplified and agile management environment, OBP opens the door to precise segmentation by occupancy.

The key question for the hotelier today is not only which to choose, but how to overcome the technical barrier that separates them: Is it possible to achieve the revenue precision of OBP with the operational agility of PDP? Can we automate complexity so it stops being a brake?

In the second part, we will analyze how connectivity is evolving to integrate both philosophies and eliminate the friction between data loading and revenue strategy.